![]()

![]() By László Antal (RWTH Aachen University) and Martin Aubard (OMST)

By László Antal (RWTH Aachen University) and Martin Aubard (OMST)

Sonars are acoustic sensors that rely on the propagation of sound to navigate or detect objects in the underwater domain. High-resolution sonars typically operate by emitting sound pulses at a high frequency, which allows for short-range scanning. Conversely, using lower frequencies extends the scanning range but decreases the resolution. By receiving and processing the signals that bounce back from encountered objects, sonars can detect the range of these objects.

There are different kinds of sonars used for various applications, categorized into two main groups: active and passive. Active sonars emit sound pulses and listen for their return, while passive sonars only listen to sounds emitted by other sources (e.g., other ships or marine life). This makes passive sonars suitable for specific applications such as submarine detection and marine-life monitoring, while active sonars can be used for broader purposes including underwater navigation, object detection, and seafloor mapping.

Active sonars are characterized by a set of main features: frequency, number of beams, minimum and maximum ranges, and horizontal and vertical apertures. Variations in these characteristics result in different sonar designs. The most well-known ones include Single-Beam sonars, Multi-Beam sonars, Forward-Looking sonars (FLS), Side-Scan sonars (SSS), and Synthetic Aperture sonars (SAS). Single-Beam sonars have one beam with a 1-degree vertical and horizontal aperture, typically used for measuring water depth. Multi-Beam sonars, while maintaining a single degree of vertical aperture, have a wide horizontal aperture that emits multiple beams in a fan-shaped pattern, making them ideal for seafloor mapping. Forward-Looking sonars have wide horizontal and vertical apertures, providing a higher level of detail from scanned environments. The output of FLS is a 2D image representing the range (distance to objects) and the beam angle, which helps visualize fine features, though 3D reconstruction using them is challenging.

SSS consists of two identical sonars scanning from both sides, each with a narrow horizontal aperture, wide vertical aperture, and high maximum scanning range. Mounted on a moving platform, SSS is used for seabed imaging, providing a high level of detail. SAS are advanced SSS that ping sound pulses at a higher rate while covering long ranges. SAS outputs are images with much higher resolution than conventional sonars, allowing for detailed examination of small objects and fine features. However, their use is limited by the strict requirement of maintaining stable movements throughout the scan.

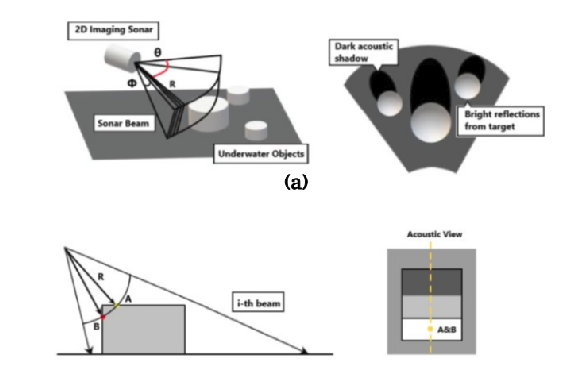

Researchers working on underwater perception have faced challenges when using specific sonar devices for applications beyond their hardware capabilities. One such challenge is using FLS for 3D reconstruction purposes. Figure 2 (a and b) illustrates how FLS emits its fan-shaped beams, the data retrieved, and the acoustic 2D representation of scanned objects. As shown in Figure 2(a), the range (R) is detected to determine how far the objects are, and the beam number represented by angle (\theta) is known. However, the vertical angle, also known as the elevation angle, is lost. Another challenge in using FLS is shown in Figure 2(b), where at a specific beam (i), a ray hitting an object at several points over the same radius (R) is represented by the same point in an acoustic image, albeit with a higher intensity. This means that several points in the actual 3D world are only represented by one point in the acoustic image.

Towards Robust and Efficient Side-scan Sonar Object Detection with YOLOX-ViT

Outline

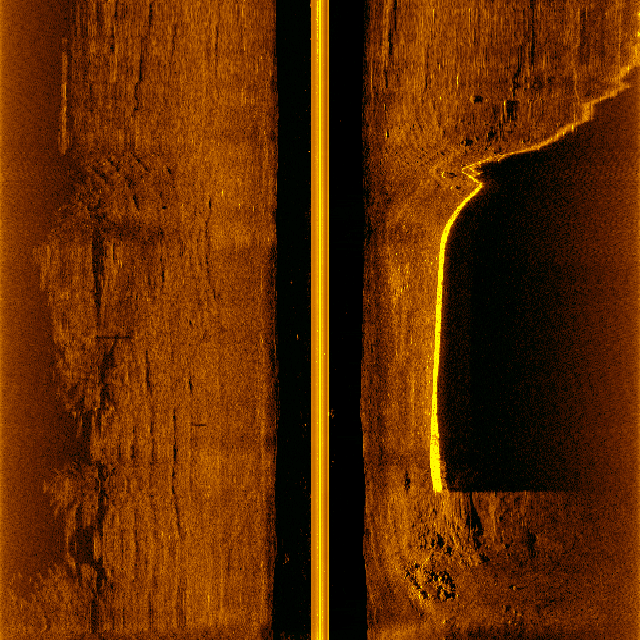

Side-scan sonar (SSS), one of the most used type of sonar, emits sound waves towards the sea floor and captures the returning echoes, creating detailed, high-resolution images (see Figure 1) of underwater landscapes. This technology is precious for detecting and identifying submerged objects, mapping the sea floor, and conducting environmental assessments. The detailed imagery produced by SSS makes it an indispensable tool in underwater exploration and research. However, the large volume of data generated by SSS necessitates automated processing techniques, where object detection algorithms come into play.

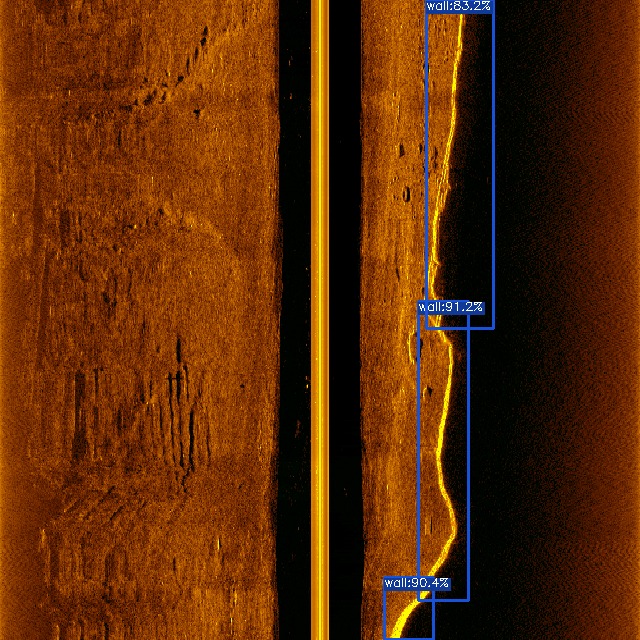

Object detection (see Figure 2) is a fundamental task in computer vision, aiming to locate and classify objects within an image. However, applying object detection to sonar images poses unique challenges due to the distinct characteristics of sonar imagery, such as noise, low contrast, and complex underwater features.

Despite the advancements in object detection algorithms, there are significant limitations when applied to SSS images. Current models often need help with the variability and quality of sonar data, leading to suboptimal performance. Additionally, traditional object detection models are computationally intensive, which can be a bottleneck for real-time applications on resource-constrained AUVs.

We introduce our work on robust and efficient side-scan sonar object detection using YOLOX-ViT to address these challenges. Our approach leverages knowledge distillation (KD) and adversarial training to enhance the model’s efficiency and robustness. Knowledge distillation allows us to transfer knowledge from a larger, more complex model to a smaller, more efficient one, improving performance without compromising speed. Conversely, adversarial training strengthens the model against potential adversarial attacks, ensuring reliable operation in diverse underwater conditions.

The primary aim of our work is to enable onboard object detection, allowing the AUV to process SSS images in real time. This onboard processing leverages the efficiency and reliability of our detection model, enabling the vehicle to modify its behavior based on the detected objects. Such capability is crucial for adaptive missions, where the AUV can make informed decisions autonomously, enhancing the overall mission success rate.

In this work, we aim to achieve two main objectives: improving the accuracy and efficiency of object detection in SSS images and enhancing the robustnes of the detections. By addressing these goals, we contribute to advancing the state-of-the-art in underwater object detection, facilitating more effective and reliable underwater exploration and monitoring.

Knowledge Distillation in YOLOX-ViT for Side-Scan Sonar Object Detection

This part of the blog post is based on the paper:

Aubard, M., Antal, L., Madureira, A., & Ábrahám, E. (2024). Knowledge Distillation in YOLOX-ViT for Side-Scan Sonar Object Detection.

ArXiv, abs/2403.09313.

Introduction

Exploring the oceanic environment has become increasingly important due to various underwater activities such as infrastructure development and archaeological explorations. Autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) play a crucial role in these tasks, enabling efficient data collection and underwater operations. However, the complex nature of underwater environments demands advanced decision-making capabilities and high situational awareness.

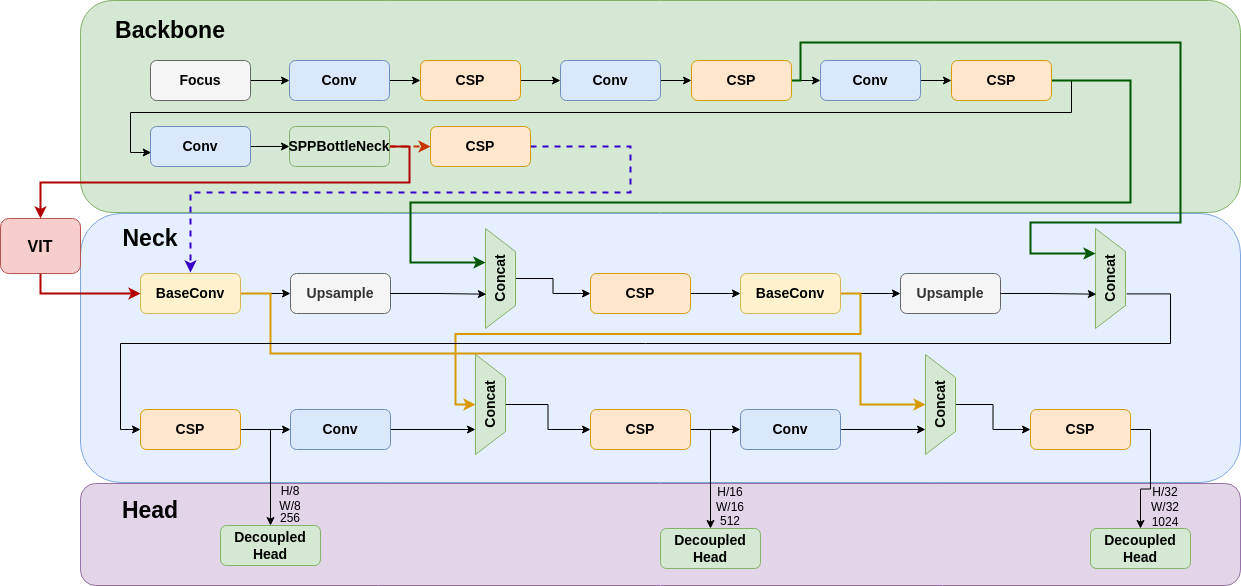

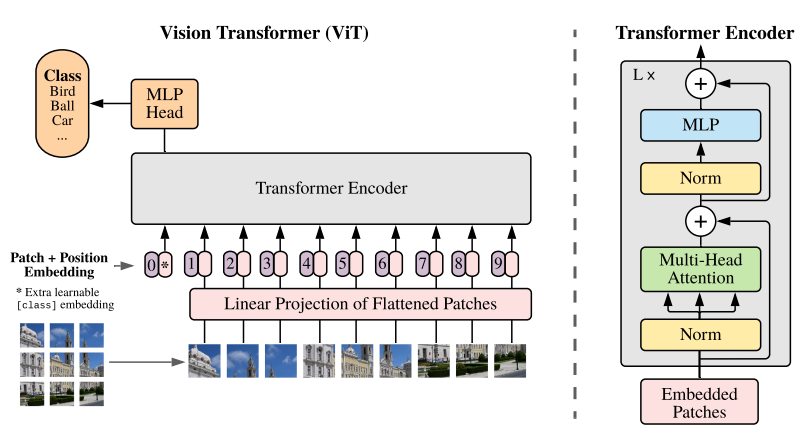

In this context, deep learning (DL) based computer vision offers a promising solution for real-time detection. Yet, the large size of standard DL models poses challenges for AUVs concerning power consumption, memory allocation, and real-time processing needs. This paper introduces YOLOX-ViT, an advanced object detection model incorporating a vision transformer layer and utilizing knowledge distillation to reduce model size without sacrificing performance.

YOLOX-ViT Model

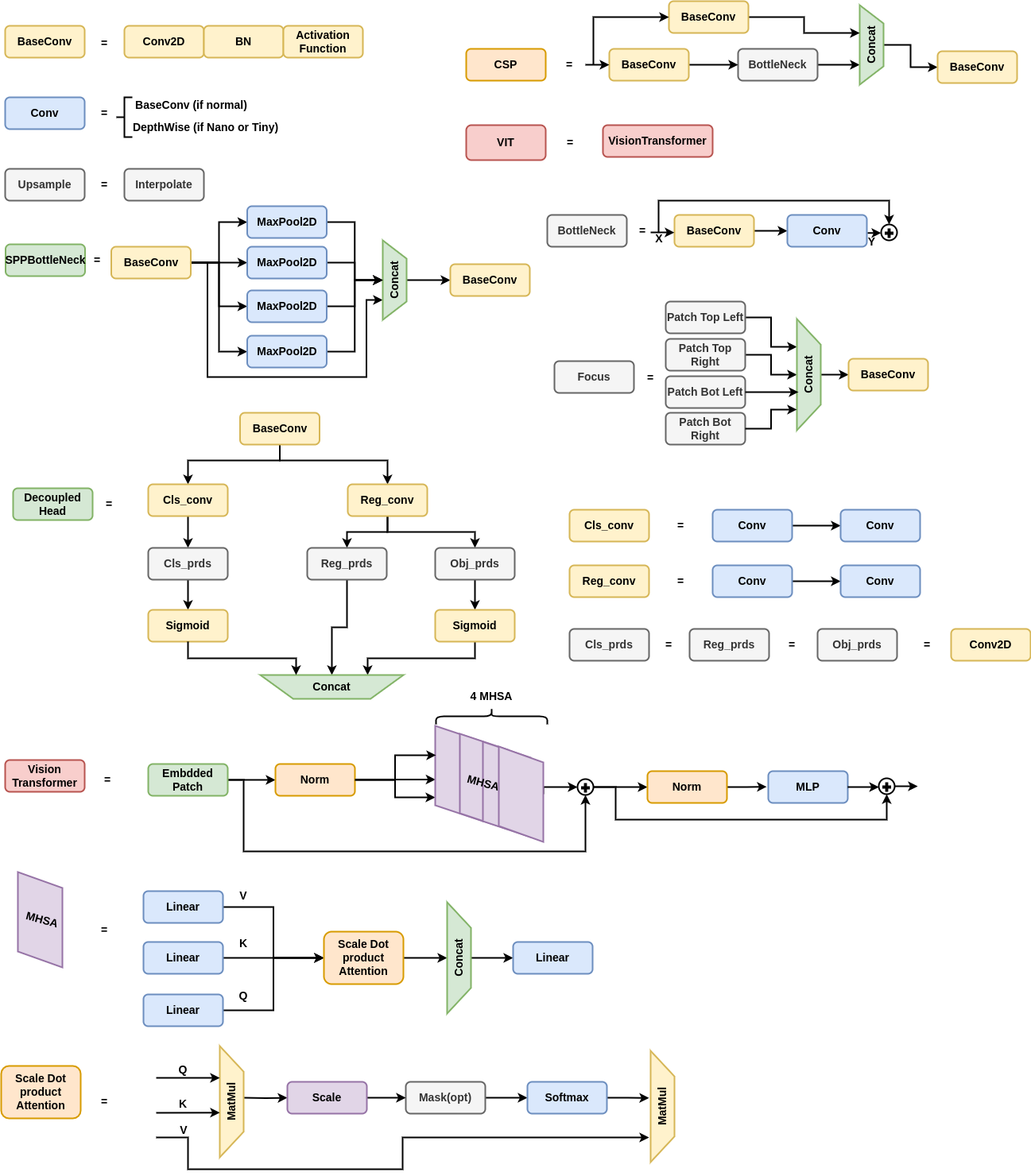

YOLOX-ViT (see Figure 5) enhances the YOLOX model by integrating a vision transformer layer (ViT) between the backbone and neck, significantly improving feature extraction capabilities. The ViT layer is configured with 4 multi-head self-attention (MHSA) sub-layers, combining the spatial hierarchy of CNNs with the global context of transformers. This integration enhances the model’s ability to detect objects in complex underwater environments.

Knowledge Distillation

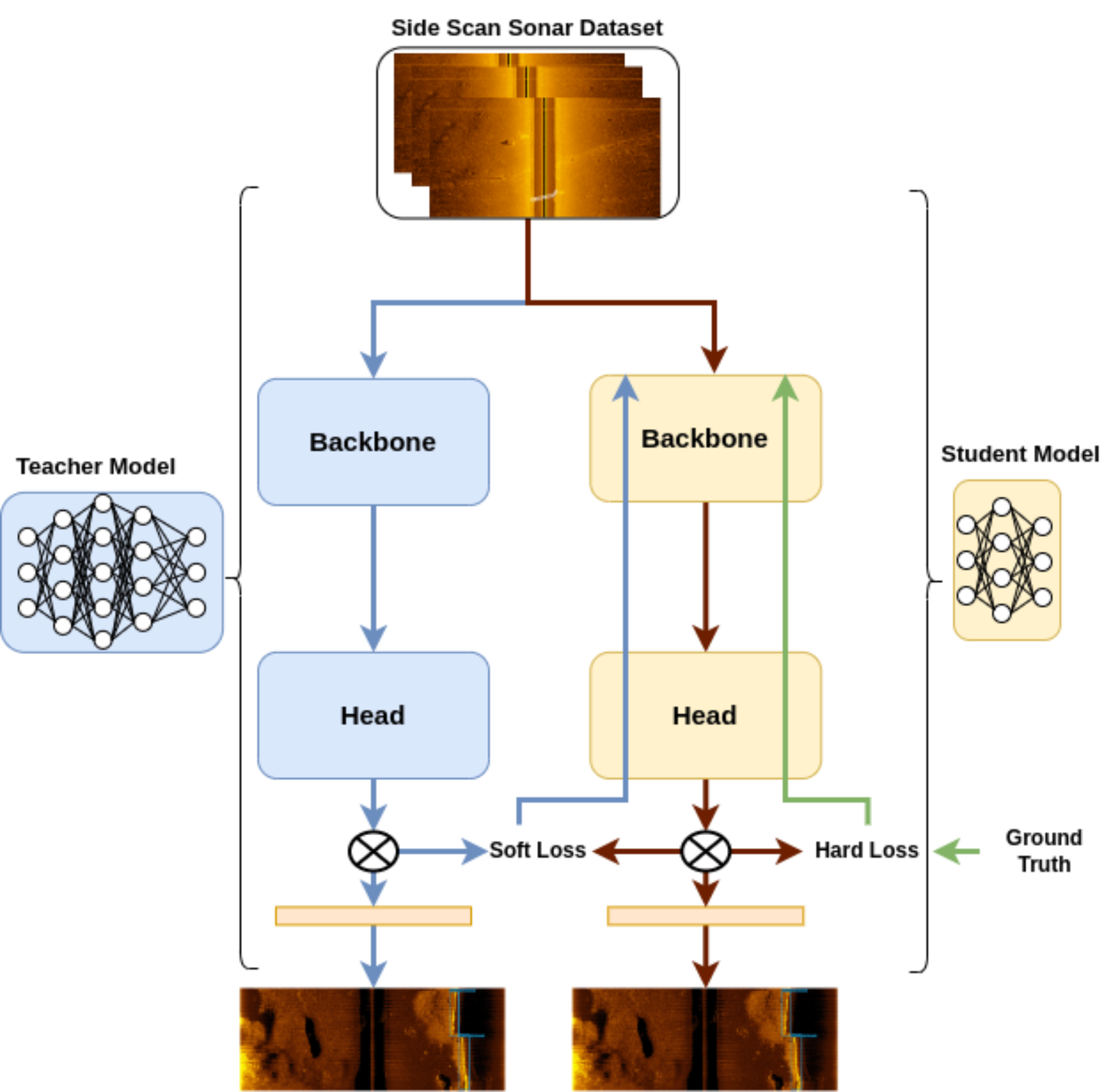

Knowledge distillation (KD) is employed to transfer knowledge from a larger, well-trained model (teacher) to a smaller model (student), using a combined loss function that incorporates both hard and soft loss components (this is visualized on Figure 7). This process allows the smaller model to learn from the nuanced behaviors of the larger model, improving its performance while maintaining a reduced size. Formally, the loss function can be expressed as:

$$

\large \mathcal{L} = \lambda_{\text{hard}}\mathcal{L}{\text{hard}} + \lambda{\text{soft}}\mathcal{L}_{\text{soft}}

$$

The KD process in YOLOX-ViT involves computing distinct loss functions for each output of the feature pyramid network (FPN), ensuring a comprehensive transfer of knowledge across classification, bounding box regression, and objectness scores. Both online and offline KD methods are explored, with the offline method reducing training time significantly. For further information, we refer to the paper mentioned above.

Using knowledge distillation, YOLOX-ViT-Nano learns directly from the logits of a pre-trained YOLOX-ViT-L model. This approach has shown a notable reduction in false positive detections by 20.35%.

Large vs. Small Models

The lack of dedicated computing resources such as GPUs is a common hindrance in deploying computer vision models in production. Large models require dedicated hardware to run in real time, while small models, though faster, suffer from reduced accuracy. Knowledge distillation allows small models to learn from larger ones, improving their accuracy while maintaining efficiency for real-time deployment on CPUs.

Sonar Wall Detection Dataset (SWDD)

For conductiong experiments, we introduce a new side-scan sonar (SSS) image dataset, the Sonar Wall Detection Dataset (SWDD). Collected in Porto de Leixões harbor using a Klein 3500 sonar on a light autonomous underwater vehicle (LAUV), the dataset includes 216 images along harbor walls. Data augmentation techniques such as noise addition, horizontal flips, and combined transformations are used to enhance the dataset’s robustness.

SWDD is completely open-access and available online on Zenodo. Accessing is possible at the following LINK.

The dataset features two classes, “Wall” and “NoWall,” with 2,616 labeled samples. The images are scaled to 640 × 640 for compatibility with computer vision algorithms, coupled with the detection labels in YOLOX and MS-COCO format.

Experimental Evaluation

The experimental evaluation of YOLOX-ViT involves training and validating the model on real-world data, including a detailed video analysis. Metrics such as true positives (TP), false positives (FP), precision (Pr), average precision at 50% IoU (AP50), and overall average precision (AP) are used to assess performance. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of YOLOX-ViT and the KD approach in reducing false positives and improving detection accuracy in underwater environments.

Conclusion

The integration of a visual transformer layer and the application of knowledge distillation in YOLOX-ViT provide a significant advancement in object detection for underwater robotics. The model achieves high accuracy with a reduced size, making it suitable for real-time implementation on AUVs. The introduced Sonar Wall Detection Dataset (SWDD) further supports research in this domain, offering valuable data for future studies.

The source code for knowledge distillation in YOLOX-ViT is available at https://github.com/remaro-network/KD-YOLOX-ViT.

Additional Material

Enhancing Model Robustness with Adversarial Examples

Introduction

Ensuring the robustness of object detection models is paramount for safe and effective underwater robotic operations. Real-world scenarios often present challenges such as noise interference, occlusions, and varying environmental conditions, which can hinder the performance of computer vision systems. To address these challenges, we introduce a novel approach leveraging the alpha-beta-Crown tool to enhance the robustness of object detection models for side-scan sonar (SSS) imagery.

The Need for Robust Object Detection

Autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) rely on accurate object detection capabilities to navigate, identify obstacles, and perform tasks efficiently in underwater environments. However, traditional models may struggle to maintain performance in the presence of noise or unexpected conditions, posing risks to mission success and equipment integrity.

Adversarial Attack Evaluation for Side Scan Sonar images Framework

Neural network verification tools such as the alpha-beta-Crown tool offer a systematic methodology to improve the robustness of neural network models. Here, the aim is to leverage the strength of neural network verification tools for object detection models. However, object detection verification is still an ongoing work because of the neural network verification tool and the computational power limitation. Thus, instead of verifying the model, another method generates adversarial attacks based on the specific SSS noises. By generating specific safety properties, such as noise thresholds and bounding box criteria, the tool facilitates the identification of vulnerabilities in the model’s predictions. This proactive approach enables us to address potential weaknesses before deployment, enhancing the model’s reliability in real-world scenarios.

Our approach involves iteratively refining the model using counterexamples generated by the Alpha-Beta-Crown tool. When safety properties are violated, indicating potential vulnerabilities, the model is retrained using the last epoch weights as a starting point. This iterative process allows the model to learn from its mistakes and adapt to challenging conditions, thereby improving its robustness.

To assess the effectiveness of the enhanced model, we subject it to adversarial attacks using Projected Gradient Descent (PGD) before and after the refinement process. Adversarial attacks simulate real-world scenarios by introducing perturbations or noise to the input data, evaluating the model’s resilience against such disruptions. By comparing the model’s performance pre- and post-refinement, we can quantify the improvement in robustness achieved through the Alpha-Beta-Crown methodology.

Throughout the refinement process, we continue to leverage knowledge distillation (KD) to transfer knowledge from larger, well-trained models to the refined model. By distilling the insights and nuances of larger models into the refined model, we further enhance its performance and generalization capabilities.

Our experimental evaluation demonstrates the efficacy of the alpha-beta-Crown methodology in enhancing model robustness. By iteratively refining the model based on identified vulnerabilities and leveraging knowledge distillation, we observe significant improvements in detection performance, particularly in the presence of noise and adverse conditions. The refined model exhibits greater resilience against adversarial attacks and demonstrates improved alignment with ground truth bounding box locations.

Conclusion

The integration of the alpha-beta-Crown tool can offers a proactive approach to improving the robustness of object detection models for side-scan sonar imagery. By systematically identifying and addressing vulnerabilities, and incorporating novel evaluation metrics and knowledge distillation, we enhance the model’s ability to maintain accurate detections in challenging underwater environments. Stay tuned for our upcoming paper on this topic.

REMARO REMARO

REMARO REMARO